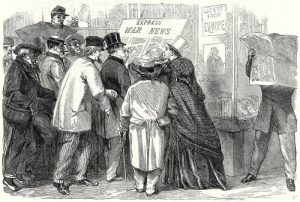

On May 18, 1864, U.S. troops marched into lower Manhattan and entered the offices of two key New York City newspapers. Soldiers leveled guns at staff members’ heads. They blocked the doors with bayonets. President Abraham Lincoln had ordered the arrest of the editors and the seizure of the newspapers. That particular May morning, the papers had run a presidential proclamation announcing a draft of 400,000 new soldiers. The problem: Lincoln had issued no such proclamation.

In the run-up to the 2020 election, American life is full of misinformation about everything from the security of mail-in voting to the causes of West Coast wildfires. Despite efforts to help citizens guard against “fake news,” curtailing misinformation remains a controversial and difficult task. But, while the platforms that help today’s untruths snowball and spread are often decidedly modern, the problem itself is nothing new. During the Civil War, Americans furiously sifted false from true during a time of extreme partisan divisions, even among those who agreed on the need to abolish slavery. They even had their own version of the Internet—the telegraph—which had exposed such stark partisan divisions in the country, its inventor Samuel Morse founded an organization to rebuild national unity. Looking at that time, it’s possible to identify key lessons for navigating this 2020 election season when accusations and false brags about the candidates abound.

You learn a lot about the egos of politicians when a Dumpster explodes in New York City. The day after a pressure-cooker bomb in Chelsea on September 17 sent the city into a frenzy, Mayor Bill de Blasio called a noon press conference to update reporters on the investigation.

You learn a lot about the egos of politicians when a Dumpster explodes in New York City. The day after a pressure-cooker bomb in Chelsea on September 17 sent the city into a frenzy, Mayor Bill de Blasio called a noon press conference to update reporters on the investigation. Planned Parenthood president Cecile Richards heard whispers that the Susan G. Komen foundation would stop funding Planned Parenthood’s breast cancer screenings from an anti-choice blog in early December. But she shrugged it off as the kind of bullying rumor that often circulates in her world. (Until Planned Parenthood, she says, “I had never worked with an organization where there were people that literally got up every day trying to figure out how to keep us from doing our work.”) Then the Komen foundation president called just before Christmas to say it was true. “It came as a total surprise,” says Richards, who requested a meeting with Komen’s board to revisit the matter but was denied.

Planned Parenthood president Cecile Richards heard whispers that the Susan G. Komen foundation would stop funding Planned Parenthood’s breast cancer screenings from an anti-choice blog in early December. But she shrugged it off as the kind of bullying rumor that often circulates in her world. (Until Planned Parenthood, she says, “I had never worked with an organization where there were people that literally got up every day trying to figure out how to keep us from doing our work.”) Then the Komen foundation president called just before Christmas to say it was true. “It came as a total surprise,” says Richards, who requested a meeting with Komen’s board to revisit the matter but was denied. An icy drizzle dampened the spare crowd of onlookers as George W. Bush wended his way to the Capitol to take the oath of office on January 20, 2001. By the time the new chief executive sat in the viewing stand to watch the inaugural parade hours later, his only fellow celebrants seemed to be the family members and longtime friends seated nearby. Empty bleachers extended to either side. Maybe the day wasn’t as frigid as the inaugural that ultimately condemned William Henry Harrison to death by pneumonia, but by most measures it was bleak.

An icy drizzle dampened the spare crowd of onlookers as George W. Bush wended his way to the Capitol to take the oath of office on January 20, 2001. By the time the new chief executive sat in the viewing stand to watch the inaugural parade hours later, his only fellow celebrants seemed to be the family members and longtime friends seated nearby. Empty bleachers extended to either side. Maybe the day wasn’t as frigid as the inaugural that ultimately condemned William Henry Harrison to death by pneumonia, but by most measures it was bleak.

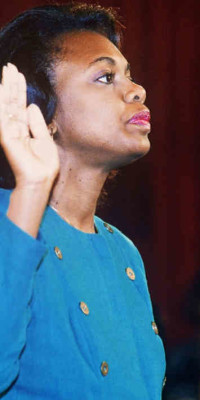

As a teenager in Oklahoma, Anita Hill showed uncanny prescience in choosing a hero for the life that awaited her: Barbara Jordan, the outspoken 38-year-old congresswoman who captivated the nation when she forcefully defended the constitution during Richard Nixon’s impeachment proceedings. “I was watching the Watergate hearings, and I thought, This is the bravest woman—and she’s from Texas? Next door to me? This black woman is out there, and she’s a star in these hearings. She’s sitting with all these guys, and she’s definitely not a shrinking violet.” The image worked for Hill, Suddenly, she could envision how “you could be in the kind of skin that I was in, maybe even come from the same background, and make an impact on the world.”

As a teenager in Oklahoma, Anita Hill showed uncanny prescience in choosing a hero for the life that awaited her: Barbara Jordan, the outspoken 38-year-old congresswoman who captivated the nation when she forcefully defended the constitution during Richard Nixon’s impeachment proceedings. “I was watching the Watergate hearings, and I thought, This is the bravest woman—and she’s from Texas? Next door to me? This black woman is out there, and she’s a star in these hearings. She’s sitting with all these guys, and she’s definitely not a shrinking violet.” The image worked for Hill, Suddenly, she could envision how “you could be in the kind of skin that I was in, maybe even come from the same background, and make an impact on the world.”