“Storytelling gives us the power to bring order to the chaos of the real under our own sign, and in this it isn’t very far from political power.” – Elena Ferrante

“Storytelling gives us the power to bring order to the chaos of the real under our own sign, and in this it isn’t very far from political power.” – Elena Ferrante

The Russian brand of fake news arrived in my life this way: In late June 2014, I was trading loving emails with a man I had been seeing. Travel had separated us, and we anxiously anticipated our reunion. These messages were sweet, down to noting the reverberation of shortening proximity.

On the eve of my return, he sent an email with an entirely different tone. He had dined with a friend. The friend had enlightened him about how the US had wronged Putin by essentially forcing him to invade Ukraine. After the dinner, the man I was dating had begun scouring the internet for more clues.

ELENA FERRANTE DOES NOT require privacy. She lays out her psychosexual-emotional range for all the world in multiple languages. She does not lock down her time, although she controls its use: one written interview in each language with each book. What she avoids is the parade, the opportunity for outsiders to evaluate aspects of her she is not ferociously driven to present. That is why she wrote a letter to her publishers in 1991, before they released her first novel, Troubling Love, before she knew whether she would find one reader or one million. In the letter, she gently refused to appear in person for press opportunities or readings. Instead, she would send her novels into the world to make their own way.

ELENA FERRANTE DOES NOT require privacy. She lays out her psychosexual-emotional range for all the world in multiple languages. She does not lock down her time, although she controls its use: one written interview in each language with each book. What she avoids is the parade, the opportunity for outsiders to evaluate aspects of her she is not ferociously driven to present. That is why she wrote a letter to her publishers in 1991, before they released her first novel, Troubling Love, before she knew whether she would find one reader or one million. In the letter, she gently refused to appear in person for press opportunities or readings. Instead, she would send her novels into the world to make their own way. Our nation has always depended on these heavyweights to guide us, but are they still with us, and if so, who are they?

Our nation has always depended on these heavyweights to guide us, but are they still with us, and if so, who are they? Editor’s note: One day after this story was published, the WNT filed a civil-rights complaint against US Soccer citing violation of the Equal Pay Act. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission will now launch an investigation.

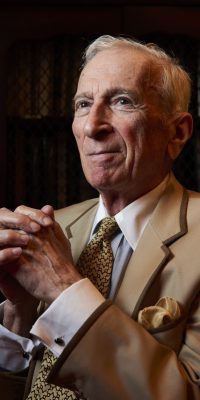

Editor’s note: One day after this story was published, the WNT filed a civil-rights complaint against US Soccer citing violation of the Equal Pay Act. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission will now launch an investigation. Gay Talese never met an interview subject he didn’t like. Or at least never one he couldn’t sympathize with. He hunts down losers, outcasts, criminals. He etches them into elegantly written books and articles that seem to normalize almost any possible human behavior. “I don’t find anything so unusual,” he says. “If you ask me, What shocks you? I can’t think of anything. I am not judgmental.” He seems almost repentant when admitting his lack of interest in reform, like an adult confiding that he can’t read. It’s a quality that makes him seem either hopelessly behind the times or far ahead of them.

Gay Talese never met an interview subject he didn’t like. Or at least never one he couldn’t sympathize with. He hunts down losers, outcasts, criminals. He etches them into elegantly written books and articles that seem to normalize almost any possible human behavior. “I don’t find anything so unusual,” he says. “If you ask me, What shocks you? I can’t think of anything. I am not judgmental.” He seems almost repentant when admitting his lack of interest in reform, like an adult confiding that he can’t read. It’s a quality that makes him seem either hopelessly behind the times or far ahead of them. THE MYSTERIOUS AUTHOR who goes by Elena Ferrante first discussed her idea for a novel that would become the now-legendary Neapolitan series with her Italian publishers over a lakeside lunch on a sunny summer afternoon in 2009.

THE MYSTERIOUS AUTHOR who goes by Elena Ferrante first discussed her idea for a novel that would become the now-legendary Neapolitan series with her Italian publishers over a lakeside lunch on a sunny summer afternoon in 2009. Tommy Safian remembers the moment he knew he needed to go for the big job.

Tommy Safian remembers the moment he knew he needed to go for the big job. John Gomes doesn’t break stride as he rushes across the black marble lobby of his West Village apartment building. He waves a strong arm to indicate I am to fall in immediately as he’s in a hurry to his day’s first meeting. Even from 50 feet away, underneath the lobby’s colossal, 24-foot ceilings, Gomes seems taller than his 6-foot-1 frame. With his shaved bald head, he resembles a more fashionable Daddy Warbucks: stylish, but not flashy, in a soft, gray felt jacket with suede elbow patches, bright tie and brown wingtips. It’s 9:30 a.m. and Gomes has an appointment downtown to discuss the details of a new condo development that could ultimately yield $113 million in contracts.

John Gomes doesn’t break stride as he rushes across the black marble lobby of his West Village apartment building. He waves a strong arm to indicate I am to fall in immediately as he’s in a hurry to his day’s first meeting. Even from 50 feet away, underneath the lobby’s colossal, 24-foot ceilings, Gomes seems taller than his 6-foot-1 frame. With his shaved bald head, he resembles a more fashionable Daddy Warbucks: stylish, but not flashy, in a soft, gray felt jacket with suede elbow patches, bright tie and brown wingtips. It’s 9:30 a.m. and Gomes has an appointment downtown to discuss the details of a new condo development that could ultimately yield $113 million in contracts. I. DREAM TRIP

I. DREAM TRIP

If Kate Moss were to open her ripe, Cupid’s-bow mouth to make a public statement, it would go something like this: “I’m not anorexic, I’m not a heroin addict, I’m not pregnant – all the shit they fucking say about me is not true. It’s a load of lies the media made.” Moss pauses for breath.

If Kate Moss were to open her ripe, Cupid’s-bow mouth to make a public statement, it would go something like this: “I’m not anorexic, I’m not a heroin addict, I’m not pregnant – all the shit they fucking say about me is not true. It’s a load of lies the media made.” Moss pauses for breath. Ask parents if they feel sorry for their childless counterparts, and the response is almost always yes. Parents know how annoying they sound singing the praises of parenthood, but they can’t help it. “What is wrong with them?” one mother I know confesses thinking of non-parents. “How empty is your life? Why do you exist?” She’s only half-joking. What childless people suspect about self-righteous parents is true: no matter how successful you are or how happy you claim to be, they pity you.

Ask parents if they feel sorry for their childless counterparts, and the response is almost always yes. Parents know how annoying they sound singing the praises of parenthood, but they can’t help it. “What is wrong with them?” one mother I know confesses thinking of non-parents. “How empty is your life? Why do you exist?” She’s only half-joking. What childless people suspect about self-righteous parents is true: no matter how successful you are or how happy you claim to be, they pity you. One day in 1934, Pinchus Kahanovitch, a fifty-one-year-old Ukrainian writer of Yiddish stories, fairy tales, and criticism, decided he did not want to disappear. Within a group of novelists and short story writers that included David Bergelson, Peretz Markish, and Moyshe Kulbak, Kahanovitch had been something of an idol, having published in the great Y.L. Peretz’s journal, Yudish, in the 1910s under the pen name Der Nister (meaning “the Hidden One”). The novelist Israel Joshua Singer later recalled a visit to Kiev around 1920 in which a member of the Culture League announced during a meeting that, “had writers of the whole world been given a chance to read Der Nister’s work, they would have broken their pens.”

One day in 1934, Pinchus Kahanovitch, a fifty-one-year-old Ukrainian writer of Yiddish stories, fairy tales, and criticism, decided he did not want to disappear. Within a group of novelists and short story writers that included David Bergelson, Peretz Markish, and Moyshe Kulbak, Kahanovitch had been something of an idol, having published in the great Y.L. Peretz’s journal, Yudish, in the 1910s under the pen name Der Nister (meaning “the Hidden One”). The novelist Israel Joshua Singer later recalled a visit to Kiev around 1920 in which a member of the Culture League announced during a meeting that, “had writers of the whole world been given a chance to read Der Nister’s work, they would have broken their pens.” Let’s say a racehorse is a gelding—in other words, the end of the line. His worth, his entire value, lies only in himself. No colts or fillies will trail him on the pedigree tree. Either he performs or he fails. He might find himself one day in an air-conditioned stall in Dubai being massaged, hoof to top line, by the best masseuse in the equine business, fed his preferred twenty-two or so pounds of oats, nine pounds of hay, and thirteen gallons of water. He might take a dip in his pool after a workout. That is, if he can run.

Let’s say a racehorse is a gelding—in other words, the end of the line. His worth, his entire value, lies only in himself. No colts or fillies will trail him on the pedigree tree. Either he performs or he fails. He might find himself one day in an air-conditioned stall in Dubai being massaged, hoof to top line, by the best masseuse in the equine business, fed his preferred twenty-two or so pounds of oats, nine pounds of hay, and thirteen gallons of water. He might take a dip in his pool after a workout. That is, if he can run.