Way, way back in 1994, one of my literary heroes, Barry Hannah, wrote a terrific profile of Johnny Cash for SPIN magazine. I recently assigned it for a nonfiction writing class I was teaching at Columbia University. I hadn’t remembered the ending, but I was surprised to be reminded that Hannah was no fool when it came to understanding our popular culture. Although the term ‘selfie’ wouldn’t come along until 2002, when everyone went crazy for the art form, Hannah could feel the pulse. Here’s the final passage in which he rejoices over Cash: Barry Hannah“And God, don’t we need him today, in the age  of pretty faces and rhyming sound bites that the generic sump hole of Nashville has become. The age when Christie Brinkley, suffering from a wrist injury after a helicopter crash on a snow-covered mountainside, takes time to hold her own camera out and take a picture of herself, which she provides to People magazine, in case we missed the agony.

of pretty faces and rhyming sound bites that the generic sump hole of Nashville has become. The age when Christie Brinkley, suffering from a wrist injury after a helicopter crash on a snow-covered mountainside, takes time to hold her own camera out and take a picture of herself, which she provides to People magazine, in case we missed the agony.

Johnny Cash is looking better than ever.”

Imagine you’ve never been to China. You don’t even know a single soul in China. And yet you set off to pitch the Chinese people on your idea for a colossal statue intended to be taller than their tallest skyscraper. Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi did exactly this when he came to America in 1871 to pitch a nation on the Statue of Liberty. It’s hard to fathom such hubris.

Imagine you’ve never been to China. You don’t even know a single soul in China. And yet you set off to pitch the Chinese people on your idea for a colossal statue intended to be taller than their tallest skyscraper. Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi did exactly this when he came to America in 1871 to pitch a nation on the Statue of Liberty. It’s hard to fathom such hubris. Thanks to Darcey Steinke for asking me to take part in the MY WRITING PROCESS BLOG TOUR, a path linking writers’ blogs in a discussion about approaches to fiction and nonfiction. Darcey has a new novel, Sister Golden Hair, coming out in the fall, and you can find Darcey’s answers to the four questions here:

Thanks to Darcey Steinke for asking me to take part in the MY WRITING PROCESS BLOG TOUR, a path linking writers’ blogs in a discussion about approaches to fiction and nonfiction. Darcey has a new novel, Sister Golden Hair, coming out in the fall, and you can find Darcey’s answers to the four questions here: The Statue of Liberty is America’s most famous symbol, yet few people could name the man who imagined, created, championed, groveled for, lost sleep over, and unveiled the colossus. The accepted history goes that France gave Liberty to America as an act of friendship, but this was not a gift from government to government. Instead, one artist envisioned a colossus. He designed her to stand in the harbor of the Suez Canal, but the deal fell through. He needed to sell his work somewhere, so he headed to America:

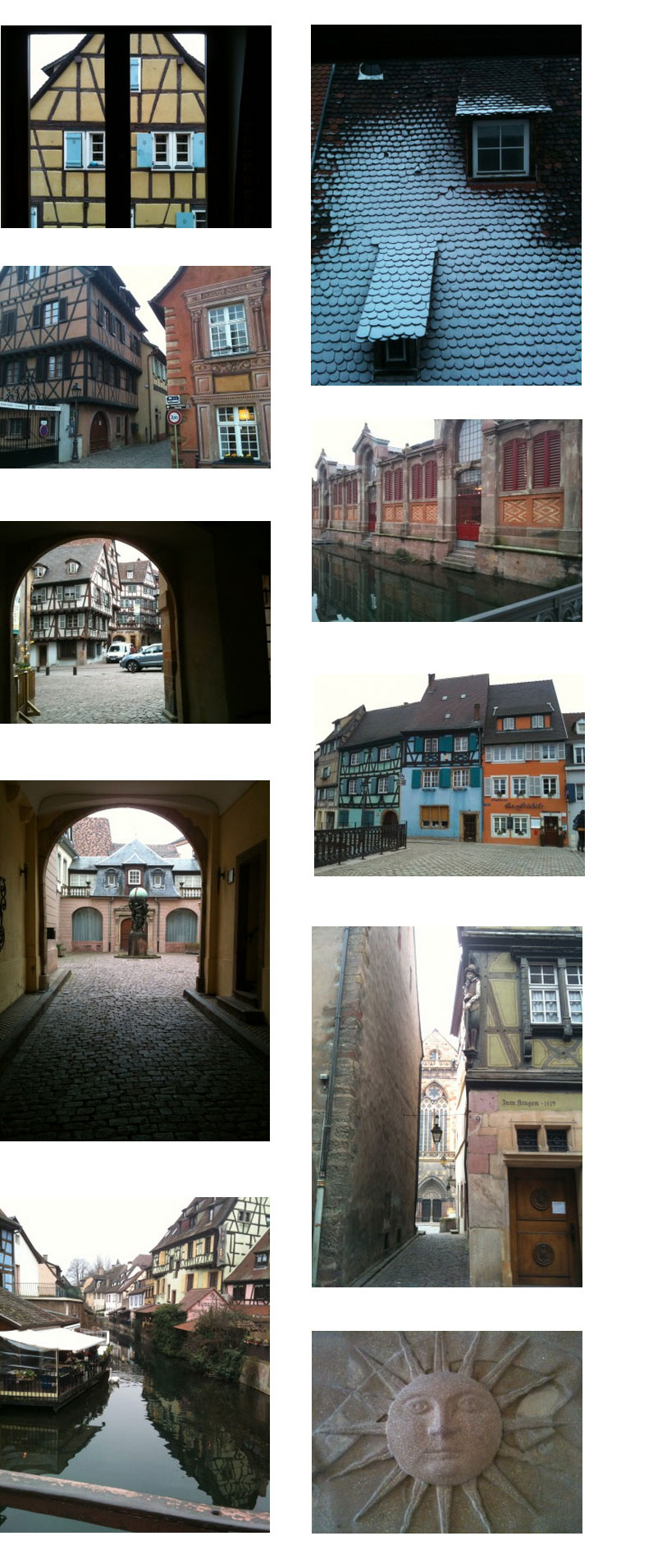

The Statue of Liberty is America’s most famous symbol, yet few people could name the man who imagined, created, championed, groveled for, lost sleep over, and unveiled the colossus. The accepted history goes that France gave Liberty to America as an act of friendship, but this was not a gift from government to government. Instead, one artist envisioned a colossus. He designed her to stand in the harbor of the Suez Canal, but the deal fell through. He needed to sell his work somewhere, so he headed to America: I was lucky enough to visit Colmar, the town where Bartholdi was born, twice during the time I researched Liberty’s Torch. His childhood home has been transformed into an impressive museum. On one floor, the historian, Régis Hueber, presided over Bartholdi’s archive of letters and diaries.

I was lucky enough to visit Colmar, the town where Bartholdi was born, twice during the time I researched Liberty’s Torch. His childhood home has been transformed into an impressive museum. On one floor, the historian, Régis Hueber, presided over Bartholdi’s archive of letters and diaries.