A mob murdered 23-year-old Abraham Franklin at 27th Street and Seventh Avenue in New York City. He had hurried to visit his mother to pray by her side for her protection when the rioters began raging from Downtown to Uptown. Just as he finished his prayers, they crashed through the door, beat him and hanged him as his mother looked on. Then they mutilated his body in front of her.

A mob murdered 23-year-old Abraham Franklin at 27th Street and Seventh Avenue in New York City. He had hurried to visit his mother to pray by her side for her protection when the rioters began raging from Downtown to Uptown. Just as he finished his prayers, they crashed through the door, beat him and hanged him as his mother looked on. Then they mutilated his body in front of her.

During the riots in July 1863, the mob also came upon Peter Heuston, a 63-year-old widowed war veteran and a member of the Mohawk tribe, whom they took to be Black. They brutally attacked him on Roosevelt and Oak Streets near the East River. He died of his injuries, leaving his 8-year-old daughter an orphan.

Another victim, William Jones, was so disfigured, whether from the mob’s mutilation or the decay his body endured waiting for observers to gain courage to investigate his identity, that he could be identified only by the loaf of bread under his arm. He had gone out to fetch the staple for his wife and never returned.

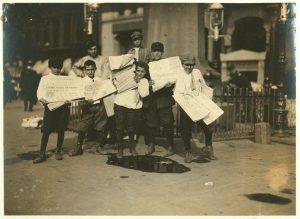

The reporters would pant up five flights of stairs to reach their dingy, dim newsrooms, where light eked through the dirt-cloaked windows and the green shades over the oil lamps were burned through with holes. They wended through hobbled tables piled high with papers, walked past cubbies so chaotically stuffed with scrolled proofs no outsider could guess the system. The reporters reeked of five-alarm smoke, or had coat pockets bulky with notes and a pistol from the front, or were tipsy from a gala ball, or dusty from a horse race. If they held important news in those notebooks, a copy boy would crowd by their elbow as they wrote, snatch the ink-wet sheets from their hands, and rush them off to the copyholder to “put them into metal.”

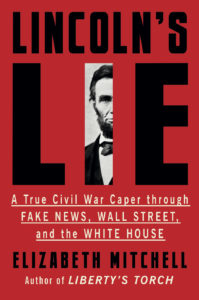

The reporters would pant up five flights of stairs to reach their dingy, dim newsrooms, where light eked through the dirt-cloaked windows and the green shades over the oil lamps were burned through with holes. They wended through hobbled tables piled high with papers, walked past cubbies so chaotically stuffed with scrolled proofs no outsider could guess the system. The reporters reeked of five-alarm smoke, or had coat pockets bulky with notes and a pistol from the front, or were tipsy from a gala ball, or dusty from a horse race. If they held important news in those notebooks, a copy boy would crowd by their elbow as they wrote, snatch the ink-wet sheets from their hands, and rush them off to the copyholder to “put them into metal.” It was just after three o’clock in the dark early morning hours of May 18, 1864, when the footsteps of a seventeen-year-old boy broke the near silence around New York’s Printing House Square. The newspaper editors had all closed up shop for the night, having received the Associated Press’s “all-in” alert, meaning that every bit of breaking news had been delivered to the papers’ offices for the day and, therefore, the morning editions could go to print. Editors Horace Greeley of the New-York Tribune, James Gordon Bennett of the New York Herald, and Henry Raymond of the New York Times—the three most powerful people in the press business—had already headed home or to social events. Lower-ranking editors had departed thereafter. Only the foremen and night managers stayed on, monitoring the churning high-powered, steam-driven presses as they rolled over the newsprint paper, preparing the news to send far and wide.

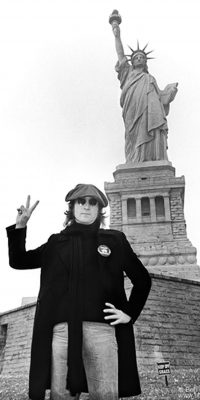

It was just after three o’clock in the dark early morning hours of May 18, 1864, when the footsteps of a seventeen-year-old boy broke the near silence around New York’s Printing House Square. The newspaper editors had all closed up shop for the night, having received the Associated Press’s “all-in” alert, meaning that every bit of breaking news had been delivered to the papers’ offices for the day and, therefore, the morning editions could go to print. Editors Horace Greeley of the New-York Tribune, James Gordon Bennett of the New York Herald, and Henry Raymond of the New York Times—the three most powerful people in the press business—had already headed home or to social events. Lower-ranking editors had departed thereafter. Only the foremen and night managers stayed on, monitoring the churning high-powered, steam-driven presses as they rolled over the newsprint paper, preparing the news to send far and wide. Who knows what Strom Thurmond had against the Beatles, but the senator from South Carolina certainly knew how to make John Lennon’s life miserable. On Feb. 4, 1972, the 69-year-old, anti–Civil Rights agitator wrote a few lines to Attorney General John Mitchell and President Richard Nixon’s aide, William Timmons, which would end up threatening Lennon with deportation and entangling him in legal limbo for almost four years.

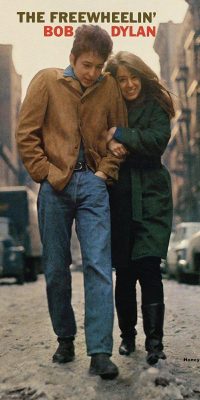

Who knows what Strom Thurmond had against the Beatles, but the senator from South Carolina certainly knew how to make John Lennon’s life miserable. On Feb. 4, 1972, the 69-year-old, anti–Civil Rights agitator wrote a few lines to Attorney General John Mitchell and President Richard Nixon’s aide, William Timmons, which would end up threatening Lennon with deportation and entangling him in legal limbo for almost four years. If you walk along Jones Street in Greenwich Village, facing W. Fourth Street with Bleecker Street at your back, you’ll find yourself in the exact spot where Bob Dylan was captured on the cover of “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan” in 1963. To experience it like Dylan did, you should go in the fading light of a February afternoon, dirty slush on the streets and a VW van parked against the curb. You should wear a suede jacket, too thin for the cold, and have your first real love braced against your arm. Around the corner, your $60-a-month apartment should await you, where you sometimes write songs — some to this first love on your arm — songs that would make you legendary the world over.

If you walk along Jones Street in Greenwich Village, facing W. Fourth Street with Bleecker Street at your back, you’ll find yourself in the exact spot where Bob Dylan was captured on the cover of “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan” in 1963. To experience it like Dylan did, you should go in the fading light of a February afternoon, dirty slush on the streets and a VW van parked against the curb. You should wear a suede jacket, too thin for the cold, and have your first real love braced against your arm. Around the corner, your $60-a-month apartment should await you, where you sometimes write songs — some to this first love on your arm — songs that would make you legendary the world over. At three in the morning on Wednesday, June 21, 1871, Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi made his way up to the deck of the Pereire, hoping to catch his first glimpse of America. The weather had favored the sculptor’s voyage from France, and this night proved no exception. A gentle mist covered the ocean as he tried in vain to spot the beam of a lighthouse glowing from the new world.

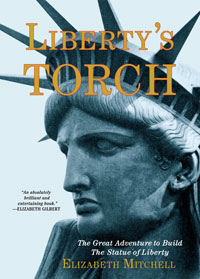

At three in the morning on Wednesday, June 21, 1871, Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi made his way up to the deck of the Pereire, hoping to catch his first glimpse of America. The weather had favored the sculptor’s voyage from France, and this night proved no exception. A gentle mist covered the ocean as he tried in vain to spot the beam of a lighthouse glowing from the new world.

ON THE MORNING of February 15, 1912, a Thursday, George Schweitzer stepped out of his doorman’s office inside the French Renaissance lobby of America’s largest hotel, the Broadway Central, in New York City. The harsh winter sun was just slanting down East Third into Broadway, and hundreds of guests hurried in and out of the hotel’s doors. The massive American flags on each of the three Gothic towers hung slack against the winter sky.

ON THE MORNING of February 15, 1912, a Thursday, George Schweitzer stepped out of his doorman’s office inside the French Renaissance lobby of America’s largest hotel, the Broadway Central, in New York City. The harsh winter sun was just slanting down East Third into Broadway, and hundreds of guests hurried in and out of the hotel’s doors. The massive American flags on each of the three Gothic towers hung slack against the winter sky.